If you work with sequencing data, you spend a lot of time dealing with file formats. This is not the glamorous part of genomics, but it’s fundamental. I’ve seen countless hours lost to simple misunderstandings about coordinate systems, quality encodings, or missing headers. This guide covers what you actually need to know about the core NGS file formats.

The Big Picture

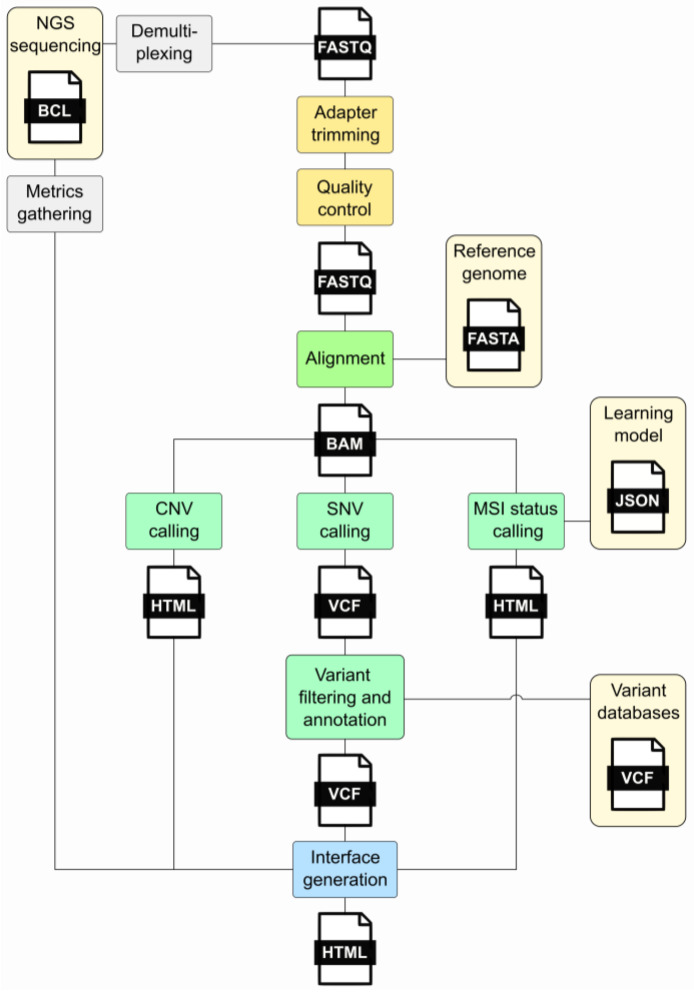

Before getting into specifics, it helps to see how these formats fit together in a typical workflow.

The three core formats – FASTQ, SAM/BAM, and VCF – have different internal structures that reflect their purposes:

FASTQ: Where It All Starts

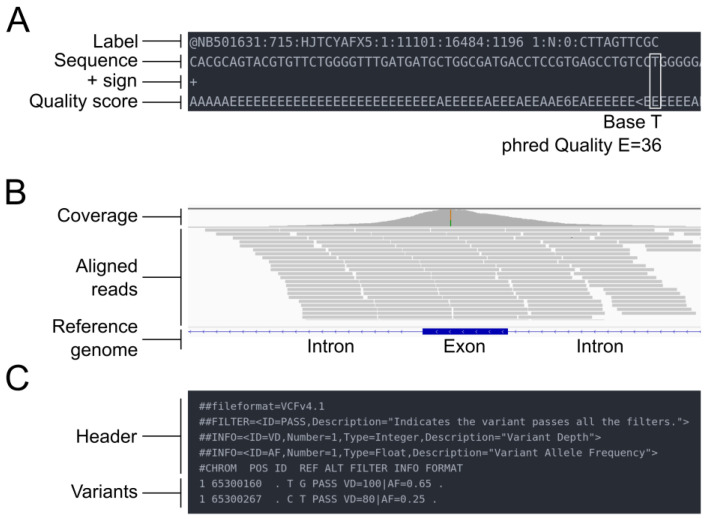

FASTQ is the starting point for most NGS work. It’s a simple format – four lines per read, repeating for millions of reads:

@SEQ_ID

GATTTGGGGTTCAAAGCAGTATCGATCAAATAGTAAATCCATTTGTTCAACTCACAGTTT

+

!''*((((***+))%%%++)(%%%%).1***-+*''))**55CCF>>>>>>CCCCCCC65

Line 1 is the identifier (starting with @). Line 2 is your sequence. Line 3 is a separator (just a + sign, sometimes with the ID repeated). Line 4 is the quality string – one character per base, encoded as ASCII.

The quality encoding has caused more confusion than any other aspect of this format. Modern Illumina data uses Phred+33, where you subtract 33 from the ASCII value to get the actual quality score. Older Illumina data (pre-1.8) used Phred+64. If you’re working with archival data, check the encoding before you start – a quick look at the quality characters usually tells you which you have. Phred+33 data will have characters like ! (Q=0) and J (Q=41), while Phred+64 data starts around @ (Q=0).

The Phred score Q relates to error probability P by: Q = -10 × log₁₀(P). A Q30 base has a 1 in 1000 chance of being wrong; Q40 is 1 in 10,000.

Practical note: Always gzip your FASTQ files. They compress well (~3-4x), and most modern tools read gzipped FASTQs directly.

Reference: Cock et al. (2010). The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores. Nucleic Acids Research, 38(6):1767-1771.

SAM/BAM: After Alignment

Once you align reads to a reference genome, you get SAM (text) or BAM (binary compressed) files. In practice, you work with BAM – it’s smaller and supports random access via indexing.

A SAM file has a header section (lines starting with @) followed by alignment records. Each alignment has 11 required fields:

| Field | What It Is |

|---|---|

| QNAME | Read name |

| FLAG | Bit flags encoding read properties |

| RNAME | Chromosome/contig |

| POS | Position (1-based, leftmost) |

| MAPQ | Mapping quality (0-60, higher is better) |

| CIGAR | Alignment description |

| RNEXT | Mate’s chromosome |

| PNEXT | Mate’s position |

| TLEN | Insert size |

| SEQ | Read sequence |

| QUAL | Quality string |

The FLAG field is a bitwise encoding that tells you a lot: Is the read paired? Is it properly aligned with its mate? Is it reverse-complemented? Is it a duplicate? You’ll find yourself consulting the SAM specification or running samtools flags until you memorize the common values (99, 147, 83, 163 for a proper pair in forward/reverse orientation).

The CIGAR string describes how the read aligns. 50M means 50 matching bases. 30M2I18M means 30 matches, a 2-base insertion, then 18 more matches. 10S40M means 10 bases were soft-clipped (present in SEQ but not aligned), followed by 40 matches. These become important when you’re investigating specific alignments or debugging variant calls.

Important: BAM files must be sorted before indexing. Sort by coordinate for most applications, by read name for some tools that process pairs together.

Reference: Li et al. (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics, 25(16):2078-2079.

VCF: Variant Calls

VCF stores genetic variants – SNPs, indels, and structural variants. It’s become the lingua franca for sharing variant data.

A minimal VCF looks like:

##fileformat=VCFv4.3

##reference=hg38

#CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INFO FORMAT SAMPLE1

chr1 12345 rs123 A G 30 PASS DP=100 GT:DP 0/1:50

The header (## lines) defines the file format version, reference genome, and importantly, the schema for INFO and FORMAT fields. The data lines have chromosome, position, variant ID, reference allele, alternate allele, quality score, filter status, INFO fields, and per-sample genotype data.

A few things that trip people up:

Positions are 1-based. Unlike BED (0-based), VCF uses 1-based coordinates. This matters when you’re converting between formats or comparing to genome browser views.

REF and ALT define the variant. For a deletion, REF might be AG and ALT is A – the position given is the base before the deletion. This “left-aligned” representation is standardized but can confuse newcomers.

The genotype (GT) field uses allele indices. 0 is reference, 1 is the first ALT, 2 is the second ALT (if present). So 0/1 is heterozygous for the first ALT allele; 1/1 is homozygous ALT.

For cancer genomics, you’ll often see tumor-normal paired VCFs with additional fields like allele depths (AD), variant allele frequency (VAF or AF), and somatic vs germline annotations.

Reference: Danecek et al. (2011). The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics, 27(15):2156-2158.

GTF/GFF3: Gene Annotations

When you need to know where genes, exons, and other features are located, you use GTF or GFF3 files. These come from annotation databases like GENCODE, RefSeq, or Ensembl.

Both are tab-delimited with 9 columns: seqname, source, feature type, start, end, score, strand, frame, and attributes. The key difference is in the attribute format and how hierarchical relationships (gene → transcript → exon) are represented.

GTF example:

chr1 HAVANA gene 11869 14409 . + . gene_id "ENSG00000223972"; gene_name "DDX11L1";

chr1 HAVANA transcript 11869 14409 . + . gene_id "ENSG00000223972"; transcript_id "ENST00000456328";

chr1 HAVANA exon 11869 12227 . + . gene_id "ENSG00000223972"; transcript_id "ENST00000456328"; exon_number "1";

GFF3 example:

chr1 Ensembl gene 11869 14409 . + . ID=gene:ENSG00000223972;Name=DDX11L1

chr1 Ensembl transcript 11869 14409 . + . ID=transcript:ENST00000456328;Parent=gene:ENSG00000223972

chr1 Ensembl exon 11869 12227 . + . ID=exon:ENSE00002234944;Parent=transcript:ENST00000456328

GFF3 uses explicit ID and Parent attributes to build the hierarchy. GTF relies on gene_id and transcript_id attributes appearing consistently. In practice, GTF is more common for RNA-seq workflows (featureCounts, HTSeq), while GFF3 is preferred for complex annotations.

Both use 1-based, fully closed coordinates – both start and end positions are included in the feature. This differs from BED’s 0-based, half-open system.

Reference: Eilbeck et al. (2005). The Sequence Ontology: a tool for the unification of genome annotations. Genome Biology, 6(5):R44.

MAF: Mutation Annotation Format

In cancer genomics, particularly from TCGA and related projects, you’ll encounter MAF files. This is the Mutation Annotation Format – not to be confused with the Multiple Alignment Format used by UCSC for comparative genomics (same acronym, different format).

MAF files are essentially annotated VCFs, but with a standardized column schema that includes:

- Hugo_Symbol (gene name)

- Chromosome, Start_Position, End_Position

- Variant_Classification (Missense, Nonsense, Frameshift, etc.)

- Variant_Type (SNP, INS, DEL, etc.)

- Reference and tumor alleles

- Sample identifiers

Example:

Hugo_Symbol Chromosome Start_Position End_Position Variant_Classification Reference_Allele Tumor_Seq_Allele2

TP53 17 7577538 7577538 Missense_Mutation C T

KRAS 12 25398284 25398284 Missense_Mutation C A

The standardized column names make it easy to combine data across studies and feed into tools like maftools for visualization and analysis. If you download somatic mutation data from cBioPortal or the GDC, it will likely be in MAF format.

Common Pitfalls

A few things worth emphasizing because they cause problems:

Coordinate systems: GTF/GFF/VCF use 1-based coordinates. BED uses 0-based. When you’re converting between formats or cross-referencing data, get this right or you’ll be off by one – sometimes in clinically relevant positions.

Sorting and indexing: BAM files need to be sorted (usually by coordinate) before indexing with samtools index. VCF files need to be bgzip-compressed (not gzip) before indexing with tabix. The index files (.bai, .tbi) must be kept alongside the data files.

Headers matter: Many tools fail silently or produce garbage when headers are malformed or missing. If a tool complains, check your headers first.

Compression: Use gzip for FASTQ, VCF, GTF/GFF. Use BAM (which is internally compressed) for alignments – don’t gzip a BAM file. For large VCFs you plan to query randomly, use bgzip + tabix indexing.

Tools You’ll Need

For each format, there’s a standard toolkit:

- FASTQ: FastQC (QC), seqtk, fastp

- SAM/BAM: samtools, Picard, IGV (visualization)

- VCF: bcftools, vcftools, IGV

- GTF/GFF: gffread, GenomeTools, bedtools (for overlap operations)

- MAF: maftools (R package)

Closing Thoughts

These formats have evolved over two decades of genomics work, and while none of them are perfect, they’re stable and well-supported. Understanding their structure will save you debugging time and help you catch problems before they propagate through your analysis.

The best way to learn these formats is to look at actual files with a text editor or less, inspect specific records, and trace them through your pipeline. When something goes wrong – and it will – this knowledge helps you identify where the problem occurred.

References

-

Cock PJ, et al. (2010). The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Research, 38(6):1767-1771. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp1137

-

Li H, et al. (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics, 25(16):2078-2079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

-

Danecek P, et al. (2011). The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics, 27(15):2156-2158. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330

-

Eilbeck K, et al. (2005). The Sequence Ontology: a tool for the unification of genome annotations. Genome Biology, 6(5):R44. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r44

-

UCSC Genome Browser. Multiple Alignment Format. https://genome.ucsc.edu/FAQ/FAQformat.html#format5

-

National Cancer Institute GDC. Mutation Annotation Format Specification. https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Data/File_Formats/MAF_Format/

For questions or comments, feel free to reach out through the lab website.

Comments