The idea that you could vaccinate against cancer has been around for over a century. William Coley was injecting bacterial toxins into tumors in the 1890s. For most of that time, the field delivered more disappointment than progress – plenty of promising early-stage data that never panned out in larger trials.

But something has changed in the past few years. The mRNA vaccine technology that got us through the COVID-19 pandemic is being redirected toward cancer, and the early results are among the most exciting data I’ve seen in immunotherapy. Let me walk through the basics, the current approvals, and where we’re heading.

Part 1: The Biology

Preventive vs. Therapeutic Vaccines

This distinction matters because the immunological challenge is fundamentally different.

Preventive vaccines are the familiar territory – you’re training the immune system to recognize a pathogen before you encounter it. For cancer, this means targeting viruses that cause cancer: HPV for cervical and other cancers, hepatitis B for liver cancer. You’re preventing the infection that would eventually lead to malignancy. This works well because viruses are foreign antigens – the immune system naturally wants to attack them.

Therapeutic vaccines are harder. You’re trying to get the immune system to attack a cancer that already exists. The tumor has been growing undetected for months or years, has established an immunosuppressive microenvironment, and is derived from the patient’s own cells. The immune system has every reason to consider it “self” and leave it alone.

Why Cancers Evade the Immune System

Tumors aren’t passive. They actively suppress immune responses through several mechanisms:

They downregulate MHC molecules, the molecular “flags” that cells use to display their internal proteins to passing immune cells. If you don’t display anything, you’re invisible.

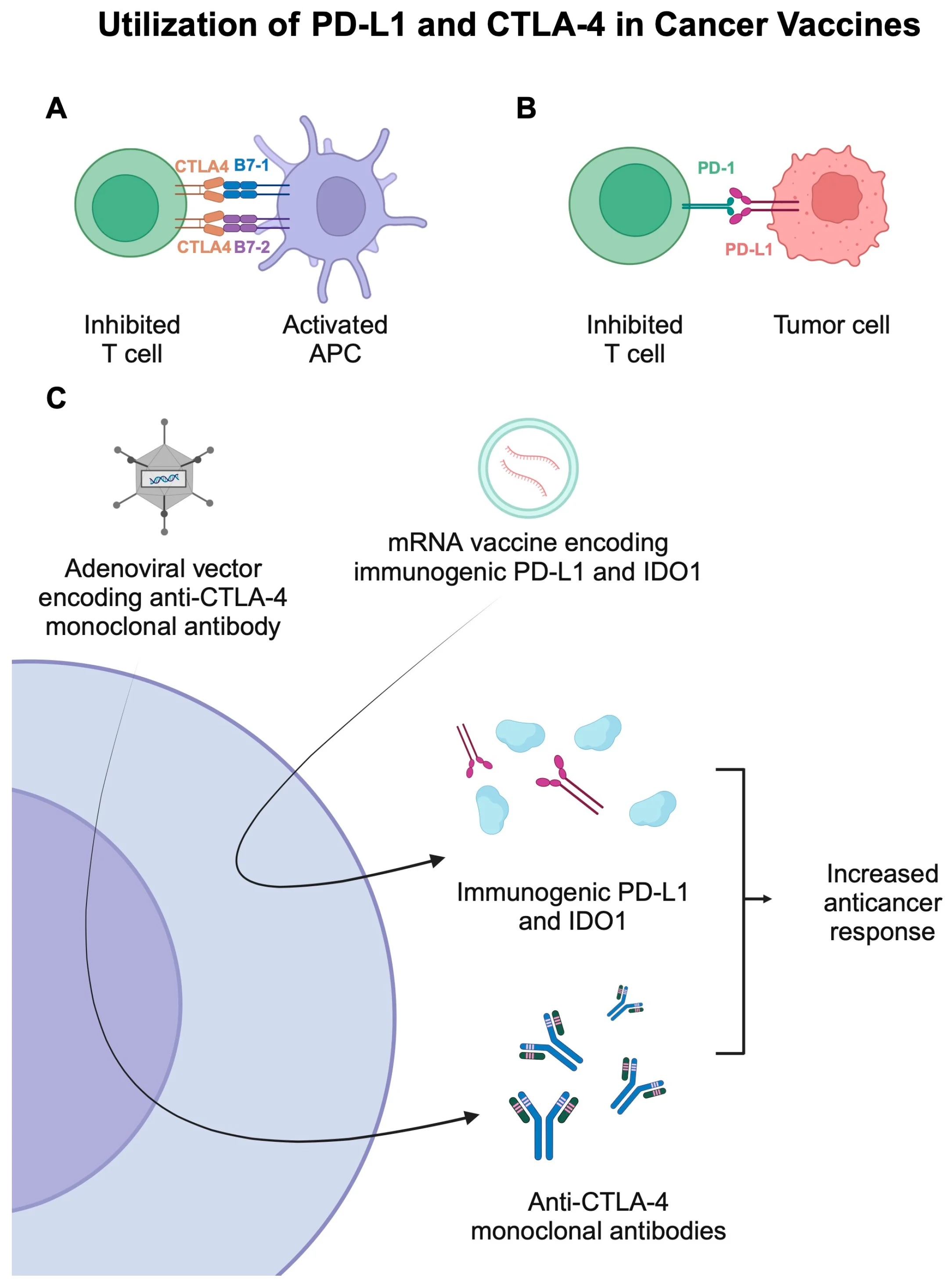

They express checkpoint ligands like PD-L1 that hit the brakes on T cells attempting to attack. The T cell sees the target but can’t pull the trigger.

They create a hostile microenvironment full of regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and inhibitory cytokines. Even T cells that make it into the tumor often become “exhausted” and dysfunctional.

A successful therapeutic cancer vaccine has to overcome all of this.

Neoantigens: The Key Target

The breakthrough insight is that cancers aren’t entirely self. The mutations that drive cancer also create abnormal proteins – neoantigens – that the immune system has never seen before. These are truly foreign antigens that arise from the tumor’s unique mutational profile.

The challenge is that every tumor is different. A lung cancer driven by KRAS G12C has different neoantigens than one driven by EGFR L858R. Even two tumors with the same driver mutation will have different passenger mutations and therefore different neoantigens.

This is why personalized cancer vaccines are so compelling: they’re designed for each patient’s specific tumor.

The Cast of Characters

To understand how vaccines work, you need to know three cell types:

Antigens are the targets – the protein fragments that the immune system recognizes. For cancer vaccines, we’re particularly interested in neoantigens (tumor-specific) and viral antigens (for virus-associated cancers).

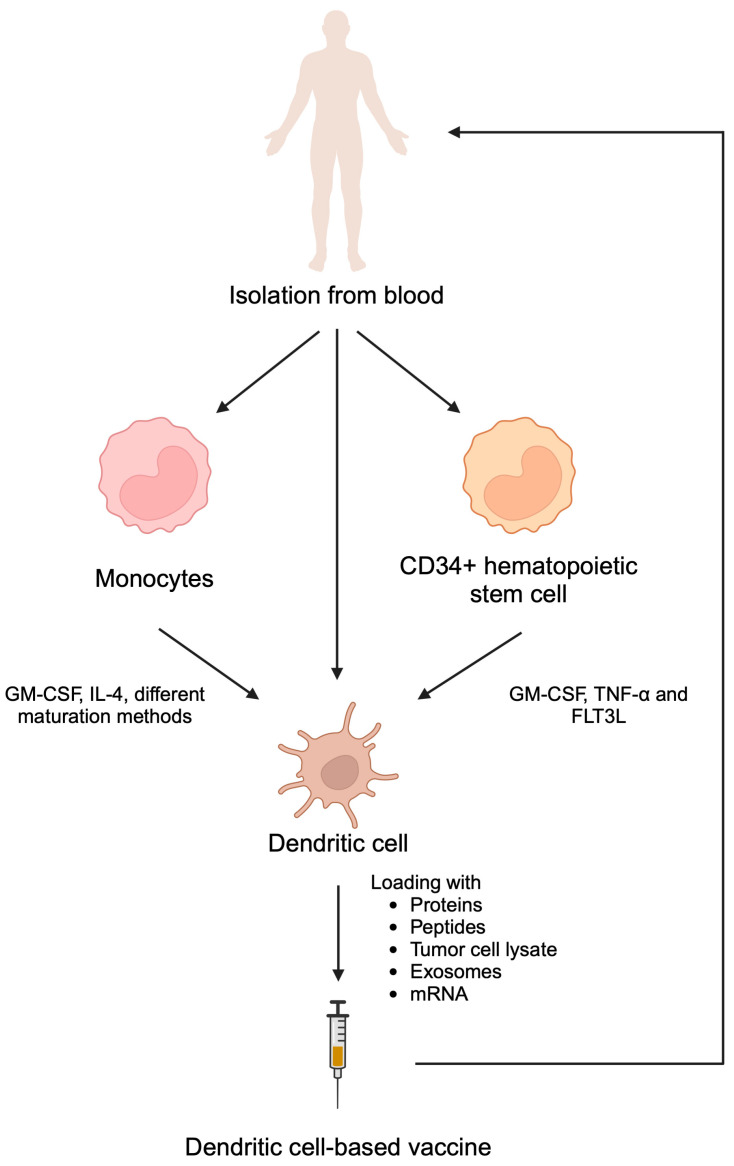

Dendritic cells are the teachers. They capture antigens, process them, and present them to T cells in lymph nodes. They’re the bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Without proper dendritic cell activation, you don’t get a robust T cell response.

T cells are the effectors. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directly kill cells displaying the target antigen. CD4+ helper T cells coordinate the broader response and help CD8+ cells function better and persist longer.

How a Cancer Vaccine Works

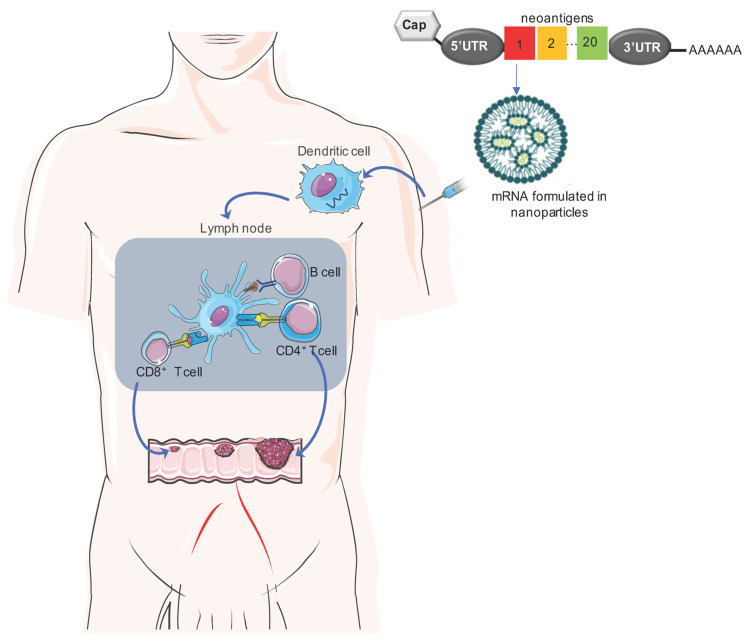

The figure below shows the mechanism for mRNA cancer vaccines, which are currently the most promising platform:

The process goes roughly like this:

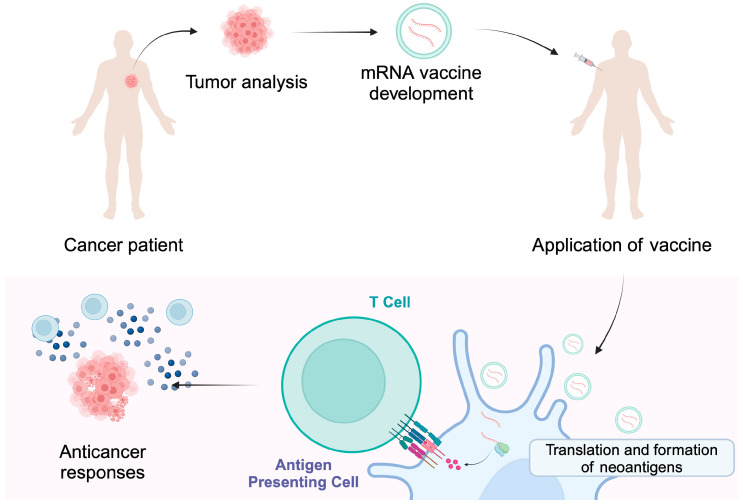

- The tumor is resected and sequenced. Algorithms compare tumor DNA to normal DNA to identify mutations.

- Computational tools predict which mutant peptides are likely to be presented on MHC molecules and recognized by T cells.

- A vaccine is manufactured encoding those neoantigens – either as mRNA, peptides, or via dendritic cells loaded with antigen.

- The vaccine is injected. Dendritic cells take up the antigen and travel to lymph nodes.

- In the lymph nodes, dendritic cells present the neoantigens to T cells, activating an immune response.

- The activated T cells leave the lymph node, circulate, find tumor cells displaying those neoantigens, and kill them.

- Some T cells become memory cells, providing ongoing surveillance.

The personalization process is illustrated below:

Vaccine Platforms

Different approaches have been tried:

| Platform | Approach | Example |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Deliver genetic instructions; cells make the antigen transiently | Moderna/Merck V940 |

| Peptide | Deliver short protein fragments directly | Various trials |

| Dendritic cell | Load patient’s own DCs with antigen ex vivo, then reinfuse | Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) |

| Viral vector | Use a harmless virus to deliver the antigen gene | T-VEC (Imlygic), Adstiladrin |

| Whole tumor cell | Use killed or modified tumor cells as the antigen source | GVAX (investigational) |

mRNA is currently the dominant platform for new development because of the speed of manufacturing and the flexibility to encode multiple antigens.

Part 2: What’s Already Approved

There are actually several cancer vaccines with FDA approval – they just haven’t lived up to the transformative potential the field hoped for. Here’s the landscape.

Preventive Vaccines

Gardasil 9 (HPV Vaccine)

| Approved 2014 | Merck |

This is arguably the most successful cancer vaccine ever made. HPV causes nearly all cervical cancers plus a substantial fraction of anal, oropharyngeal, vaginal, vulvar, and penile cancers. Gardasil 9 protects against 9 HPV strains and prevents approximately 90% of HPV-related cancers.

Countries with high vaccination coverage are already seeing dramatic declines in cervical cancer incidence. Scotland, for instance, has reported near-elimination of cervical cancer in vaccinated cohorts. This is public health at its best.

Hepatitis B Vaccine

| Approved 1986+ | Various manufacturers |

Chronic hepatitis B infection leads to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The HBV vaccine prevents infection and thereby prevents the downstream liver damage. Universal HBV vaccination programs in Asia have already begun to reduce liver cancer incidence.

Therapeutic Vaccines

Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) – Prostate Cancer

| Approved April 2010 | Dendreon |

This was the first therapeutic cancer vaccine to receive FDA approval, and it remains the only autologous cell-based cancer vaccine on the market.

The process is cumbersome: you collect the patient’s white blood cells via leukapheresis, ship them to a manufacturing facility where they’re incubated with a fusion protein (PAP-GM-CSF) to activate dendritic cells against prostatic acid phosphatase, then ship them back and infuse them. This happens three times over about a month.

In the IMPACT trial, sipuleucel-T improved median overall survival by about 4 months (25.8 vs 21.7 months) in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. That’s a real benefit, but the complexity and cost limited uptake. The broader significance was proof-of-concept: you could train the immune system to fight an existing cancer.

Reference: Kantoff PW et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411-422.

Talimogene Laherparepvec / T-VEC (Imlygic) – Melanoma

| Approved October 2015 | Amgen |

T-VEC is an oncolytic virus – a genetically modified herpes simplex virus engineered to selectively replicate in tumor cells, lyse them, and release tumor antigens. It also produces GM-CSF to attract dendritic cells to the site.

The vaccine-like mechanism is the abscopal effect: by killing tumor cells and creating inflammation in injected lesions, T-VEC can prime an immune response against distant, non-injected tumors. In the OPTiM trial, the durable response rate was 16.3% vs 2.1% with GM-CSF alone, and some patients had responses in uninjected lesions.

The limitation is that T-VEC only works for accessible lesions – it’s injected directly into tumors you can see or feel. It hasn’t shown benefit for visceral metastases. Still, for patients with injectable melanoma lesions, it provides an immunotherapy option that can synergize with checkpoint inhibitors.

Reference: Andtbacka RH et al. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2780-2788.

Nadofaragene Firadenovec (Adstiladrin) – Bladder Cancer

| Approved December 2022 | Ferring Pharmaceuticals |

This is the first adenoviral vector gene therapy for cancer. It’s a non-replicating adenovirus that delivers the interferon-alpha gene directly into bladder cells. You instill it via catheter; the bladder cells take up the vector and produce high local concentrations of IFN-alpha, activating immune cells to attack residual cancer.

The indication is BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. BCG (the tuberculosis vaccine) has been used for decades as intravesical immunotherapy – it’s one of the oldest cancer immunotherapies. But when BCG fails, patients face radical cystectomy. Adstiladrin provides a bladder-sparing alternative, with a 51% complete response rate and 46% maintaining response at one year.

Reference: Boorjian SA et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):107-117.

BCG – Bladder Cancer

Approved 1990

Worth mentioning here because BCG is one of the most successful cancer immunotherapies, even if it’s not typically described as a “vaccine” in the modern sense. It’s a live, weakened tuberculosis bacterium instilled into the bladder, where it triggers a robust local immune response. BCG reduces recurrence by 30-40% and remains standard of care for intermediate and high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Part 3: The mRNA Revolution

The approved vaccines above have had limited impact on the broader oncology landscape. But the current wave of mRNA cancer vaccines is different. The technology has matured, we’ve learned from COVID-19, and the early clinical data are striking.

Moderna/Merck – mRNA-4157 (V940)

| Phase 3 trials ongoing | Breakthrough Therapy Designation |

This is the furthest along. The approach: after surgical resection, sequence the tumor and normal tissue, identify up to 34 patient-specific neoantigens, synthesize a custom mRNA encoding all of them, deliver via lipid nanoparticles, and combine with pembrolizumab.

The KEYNOTE-942 Phase 2b results in resected high-risk melanoma were remarkable:

| Outcome | V940 + Pembrolizumab | Pembrolizumab Alone |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of recurrence/death | Reduced 49% | Reference |

| Risk of distant metastasis | Reduced 62% | Reference |

| 2.5-year recurrence-free survival | 74.8% | 55.6% |

| 2.5-year overall survival | 96.0% | 90.2% |

These are the first randomized data showing that a personalized cancer vaccine adds benefit on top of checkpoint inhibitors. The 49% reduction in recurrence risk is clinically meaningful. Three Phase 3 trials are now underway:

- INTerpath-001: Melanoma (~1,089 patients) NCT06077760

- INTerpath-002: Early-stage NSCLC NCT05933577

- INTerpath-009: Neoadjuvant NSCLC

If the Phase 3 data hold up, we could see the first personalized mRNA cancer vaccine approval by 2027-2028.

Reference: Weber JS et al. Lancet. 2024;403(10427):632-644.

BioNTech – Autogene Cevumeran

| Phase 2 ongoing | Pancreatic cancer |

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is one of the deadliest cancers. Even after complete surgical resection, most patients relapse and die within two years. The 5-year survival rate is dismal.

BioNTech’s approach combines personalized mRNA vaccine (up to 20 neoantigens) with atezolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) and chemotherapy. The Phase 1 results, published in Nature, were intriguing:

Of 16 patients, 8 generated strong T-cell responses to the vaccine (“responders”). Among responders, only 2 of 8 had recurrence over 3 years. Among non-responders, 7 of 8 recurred.

Even more striking: the vaccine-induced T cells were still detectable nearly 4 years later. This suggests durable immunological memory.

The Phase 2 IMCODE-003 trial is now enrolling ~260 patients. If the results hold, it would be transformative for a disease with essentially no good options.

Reference: Rojas LA et al. Nature. 2023;618(7963):144-150.

BioNTech – BNT113

| Phase 2 ongoing | HPV+ head and neck cancer |

Unlike the personalized vaccines above, BNT113 is an off-the-shelf mRNA vaccine targeting HPV16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. Because these are viral antigens, they’re inherently foreign and immunogenic.

In combination with pembrolizumab for recurrent/metastatic HPV16-positive head and neck cancer, early data showed a 47% response rate. The AHEAD-MERIT trial continues.

Part 4: Why Now?

Several things have converged to make this moment different:

The mRNA platform is validated. Billions of COVID-19 vaccine doses established the safety profile and the manufacturing infrastructure. The same lipid nanoparticle technology is now being applied to cancer.

Sequencing is fast and cheap. Whole exome sequencing costs a few hundred dollars and takes days. That makes personalized neoantigen identification practical at scale.

Neoantigen prediction algorithms have improved. Machine learning models now do a reasonable job of predicting which mutant peptides will be presented on MHC molecules and recognized by T cells. Not perfect, but better than a few years ago.

Checkpoint inhibitors provide the combination partner. Cancer vaccines are much more effective when combined with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. The vaccine generates the T cells; the checkpoint inhibitor removes the tumor’s ability to suppress them. This one-two punch is at the heart of the V940 success.

The adjuvant setting is ideal. Vaccines work best when tumor burden is low. After complete surgical resection, you’re dealing with microscopic residual disease rather than bulky tumors. This is exactly when the immune system has the best chance of mopping up remaining cells before they establish a recurrence.

Summary Table

| Vaccine | Type | Cancer | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gardasil 9 | Preventive (HPV) | Cervical and other HPV-related | Approved 2014 |

| Hepatitis B vaccines | Preventive (HBV) | Liver cancer | Approved 1986+ |

| BCG | Therapeutic (live bacteria) | Non-muscle invasive bladder | Approved 1990 |

| Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) | Therapeutic (dendritic cell) | Metastatic prostate | Approved 2010 |

| T-VEC (Imlygic) | Therapeutic (oncolytic virus) | Injectable melanoma | Approved 2015 |

| Adstiladrin | Therapeutic (viral vector) | BCG-unresponsive bladder | Approved 2022 |

| V940 (Moderna/Merck) | Therapeutic (personalized mRNA) | Melanoma, NSCLC | Phase 3 |

| Autogene cevumeran (BioNTech) | Therapeutic (personalized mRNA) | Pancreatic | Phase 2 |

| BNT113 (BioNTech) | Therapeutic (off-the-shelf mRNA) | HPV16+ head and neck | Phase 2 |

Looking Forward

The vision is straightforward: you have a cancer surgically removed; within weeks, a personalized vaccine is manufactured based on your tumor’s specific mutations; combined with checkpoint inhibitors, it trains your immune system to hunt down and eliminate any remaining cancer cells; memory T cells persist for years, providing ongoing surveillance.

We’re not there yet. The Phase 3 data need to mature. Manufacturing needs to scale. We need to understand which patients benefit most, which tumor types are amenable, and how to optimize the combination regimens.

But for the first time, the path forward is clear. More than 120 RNA-based cancer vaccine trials are currently active worldwide. The first approval could come as early as 2027-2028.

If this works out, it would represent a genuine paradigm shift – not just another drug, but a new way of thinking about cancer treatment as something personalized to each patient’s unique tumor.

Further Reading

- FDA – Clinical Considerations for Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines (Guidance)

- FDA – PROVENGE

- FDA – IMLYGIC

- FDA – Adstiladrin Approval

- AACR – What Is a Cancer Vaccine?

- Nature – Cancer Vaccines Outline (2024 Infographic)

- NCI – Neoantigen Vaccines Keep Cancer at Bay

- Ni L. Advances in mRNA-Based Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines. 2023;11(10):1599 (Figure 1 source)

- Kielbowski K et al. Recent Advances in Anti-Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines. 2025;13(3):237 (Figures 2-4 source)

This is for educational purposes, not medical advice. Discuss any treatment decisions with your oncologist.

Comments